NOTE: The Cult performs three times during SXSW in Austin this week. Two of the three shows are free to the public. Info below. The band is promoting its upcoming new album, “Choice of Weapon,” due May 22.

By Metal Dave

If there’s common ground between an intellectual and a rock star, the stereotype would tell you it’s lost in the cracks of an earthquake. Bob Geldof is an intellectual. Tommy Lee is a rock star. See the gap? Watch your step!

And then there’s Cult singer, Ian Astbury. Known for being deeply philosophical, earthy and highly spiritual, Ian seems to have all the outward qualities of an esoteric interview. At best, he could be agenda-driven and intimidating. At worst, he could be humorless, boring and “cosmic.” Uh-oh …

Reached at his Los Angeles home, Ian turns out to be a fantastic conversationalist. He’s astutely aware and worldly, but he’s also gracious and funny (his Ray Manzarek impersonation is fall-down deadly). Interesting, cool and much more grounded than expected, Ian is nothing if not intriguing.

With my official interview assignment allowing only 500 words, the cutting-room floor could trip you with diamonds.

What follows, then, is not so much a proper interview as it is a compilation of conversation. It also is not intended (by any stretch) to be a career retrospective. Yes, I’m aware of the Cult’s “Sonic Temple.” No, we did not discuss it.

Instead, I share the following free-flowing glimpses into the mind and soul of Ian Astbury. The standard soundbites are available elsewhere. This one is for Ian’s fanatics.

On SXSW

It’s gone from being a village to being a metropolis. It’s unbelievable. Everybody and their dog is trying to get in there. The great thing is finding out what other bands are playing. There’s a band called the Black Ryder performing that are great friends of ours that we’ve toured with. They’re doing three shows. I’ll be out watching Black Ryder. I’ve heard Bonaparte are playing from Berlin …

At what point does an experience inspire your lyrics?

Probably when there’s an emotional response and an emotional connection to an observation or feeling. It’s more that than an intellectual (response). One thing about being a musician is we travel a LOT. I’ve spent a good chunk of my life moving whether it’s on a plane or a train or whatever. You live a very nomadic lifestyle and through that — because you’re not consistently in the same environment — that also affects your perspective and the way you relate to experiences and situations. Again, I go back to the emotional connection. It’s pretty much a visceral connection to an event or an observation. That’s the point when the pen hits the paper. Or more likely, the fingers hit the keyboard.

How do you convey your lyrical intent to Billy so that you get the proper music to accompany your message?

I have the advantage of being able to pick through his musical ideas and marry them to lyrical ideas or lyrical sentiments. Sometimes a piece of music will evoke a lyric. Sometimes I may just have a title. I work a lot with working titles where you kind of have a feeling, but you don’t quite know what you want to say yet. We don’t know where the songs gonna go, but he comes about and the music and the lyrics develop at the same time. That’s when you get excited, because you don’t know what the end result is going to be. You have a feeling it’s going to go somewhere, then you take it on a journey and then you end up in a place you never expected to arrive at.

One thing about this record (“Choice of Weapon”) is we worked very thoroughly through the songs to the brink of nearly destroying them and then bringing them back. Some of the songs came instantaneously and some songs had to evolve. I think we went back to a place of instinct. There were no predetermined agendas. We’ve had periods of stagnation and being stale and repeating ourselves, but I think that’s common. With ‘Choice of Weapon,’ we just said, ‘Fuck it! We’re going to grab every jewel we can find. We’re going to play the ace and go as deep as we can.’ There’s definitely hard rock moments on this record, but then again, there’s moments that are kind of pastoral. We worked completely on what we were feeling in that moment. We weren’t trying to recreate any other period. We were just going for what was authentic, natural

Is it unfair to call the Cult a hard rock band?

It’s a double-edge sword in some ways. The hard rock community I find to be very salt of the earth. The hard rock community and the hip-hop community have got so much in common in the sense that it’s really the music of the working class people. The post-modern crowd? Slightly more erudite, slightly more self-conscious, slightly more concerned with putting something over a little more elevated, a little more considered. Great rock’n’roll and great hip-hop comes out of an environment that forces you to be more driving and aggressive. You’re not really sitting around with acoustic guitars and crying about your girlfriend. This is music about survival and the realities of the environment you come out of. There’s an authenticity in that.

On the Cult’s evolution from post-modern to hard rock and beyond

We came to the United States in 1984 with the “Dreamtime” record and … The band was very much entrenched in the genesis of the American post-modern scene … and then we came back and did another tour with the “Love” album. The CMJ Awards gave us Single of the Year for “She Sells Sanctuary.” We were on “Saturday Night Live.” We were very much an independent, post-modern band. But as soon as people started putting that tag or that stigma on us, we very naturally gravitated toward something else, because we’d done that, we’d said that.

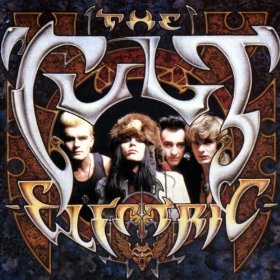

(For “Electric”) We were at Electricladyland Studios in New York City with Rick Rubin in 1986 and we were surrounded by the Def Jam family. Our sound became very direct. New York City was a very direct city. There’s no room for ambiguity in New York City (laughs). You were either straight-up or you were thrown out with the trash. We were only 25-years-old when we made that record.

AC/DC?: Breakthrough album, “Electric” had a harder rocking undercurrent thanks to the gritty influence of New York City.

We did the rock’n’roll with “Electric” and then we were on to the next thing, because for me … the Rolling Stones did it better than anybody, the New York Dolls did it better than anybody, so why would we want to go in that space? We were trying so much to find our own voice, to become better as musicians, to become better crafted and create our own vision. Here we are now making “Choice of Weapon,” and we’re still growing and still developing, we’re still students, we’re still inquisitive, we’re still passionate. I still think that what we’re doing is relevant. We still have an awareness of what’s going on around us. It’s not like I live in a cave.

So, what exactly is a Love Removal Machine?

At the time it was a metaphor for (long pause) the music industry, corporate mentality, material mindsets. I think when you live in the modality of taking … We started off as punk rock kids. We literally came out of the late 70s punk rock scene in our teens. By the time we were 23 years old, we’d already been around this stuff for eight or nine years. Everybody was, like, “Why’d you change your sound, man?” We evolved. We wanted something else. We’d done that and we’d said everything we wanted to say in that moment. The music became more aggressive and, then through touring, the rose-tinted glasses of youth and the optimism got torn away and we found ourselves in the depths of an industry and a brutal touring schedule and we were certainly surrounded by individuals and energies that were pretty much all about serving themselves and taking. Love removal machine, prostitution. The two oldest professions in the world are being a mercenary and being a prostitute. Ultimately, it’s about material…

Was Guns N’Roses a corrupting influence on the “Electric” tour?

Actually, the opposite is true. They were the understudies. We’d already been at it for six or seven years. We cut our teeth through post-industrial punk rock Britain, we’d gone through Europe, we’d already been through several United States tours with bands that had junkie tour managers (pulling) revolvers after midnight. On that tour, I was the guy getting chased by the cops.

Are you telling me the Cult was a bad influence on GN’R?!

I wouldn’t say we were a bad influence, because they were already locked and loaded. They were already bad boys. The difference is, with the Cult, we never bragged about it. The braggadocio of, like, “Hey, I’m a badass …” It wasn’t really in our lexicon, because for me, I didn’t really want to be perceived as just … that was it … that was all I had. That tour was one of the most amazing tours to be a part of.

I have great respect and admiration and love for those guys. We came up through the same time and they went through the roof! “Sweet Child O’ Mine” went through the roof and I think I completely understand Axl’s desire to have been reclusive and perhaps act out the way he’s acted out in the past. I have a lot of empathy for them. You put any young man in a situation where all of a sudden you come from a volatile upbringing and you’re the lowest thing on the totem pole, and then all of a sudden everybody’s putting you out there and going, “Now you’re No.1 and we love you!” You’re, like, “What?” Your head spins too much.

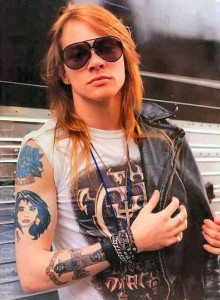

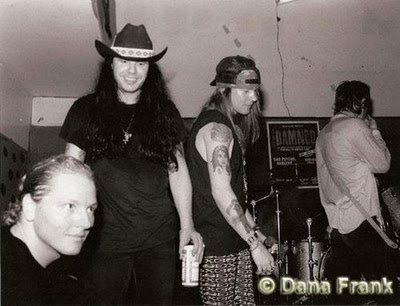

FIRST SHOT: Axl Rose sports a Cult T-shirt in honor of the band that pulled the trigger on GN’R’s upcoming stardom.

I saw Guns N’ Roses at the Marquee in London in, like, March of ’87 and I said to my manager, “We have to play with this band. They’re amazing.” I just felt such a kinship with them and where they were going. And also our ages, our passions, our interests … they were unabashedly, unabashedly embracing hard rock, glam rock, punk rock. They were right in the same psychic space as we were.

As it evolved, they were the opening act because I picked them and I pushed for them. I had to push for this band! I had to fight for this band! People were telling me, “Are you f**king kidding me?” I’d be doing radio interviews and (the deejays) would say, (in perfect stoner-dude cadence) “Hey, great to have you here. So, what are you listening to?” I’d be, like, “Uh, Guns N’Roses, they’re performing with us.” And they’d be like, “Oh, wow, we don’t play them here.” And I’d be, like, “Why not?” Of course, in hindsight, everyone’s got rose-tinted glasses. There’s been several books … Slash’s book came out and there was a book on Guns N’ Roses where they talk about the Cult and the tour … and I’ve heard things, like, we tried to screw with their sound at one show. Are you kidding? Are you kidding me? I would go out and champion this band at every single opportunity I got. There’s a camaraderie that we’ll have that nobody else will ever experience. My girlfriend at the time straightened Axl Rose’s hair and put one of my bandanas on his head and that became his look. That was my look!

What was it like touring the world in your early 20s?

We were kids, man. You give the kids the keys to the liquor cabinet when the parents leave the house, what do you expect is gonna happen? Especially, dysfunctional kids! I was 19-years-old when I started this. I grew up on the road. I grew up on tour buses. I grew up in airports and hotels. There’s a point when you’re out there for so long that you realize your family’s gone. Your family becomes your family on the road, but everybody on the road is as insane, introverted, extroverted, narcissistic as everybody else so there’s no real ground. You’re just responding to 22 hours of sitting around every day waiting for that two hours of performance. It’s not that hard being on stage. The hard part is dealing with the life.

Singing for the Doors must’ve been a dream gig for you. Yes or no?

Absolutely. Ray and Robbie are my mentors, my heroes, my benefactors. They gave so much. It was such an incredible experience performing with Ray and Robbie. I felt very grateful to be in that environment. It was nothing short of magical. Here I am being a fan from the outside and all of a sudden, I’m on the inside. Initially, I approached it with so much reverence that I was almost not able to connect. That was about the eighth or ninth show and I think it was (music critic) Jon Pareles from the New York Times who butchered our eighth performance. I looked at that and went, “The gloves are off!” Ray and Robbie were very cool about it. They knew it would take some time for the chemistry to click and when it did, we went on to do 150 shows. The demand was there.

When I was touring with Ray and Robbie, we’d go to Europe and Ray would say, (adapting a perfect Manzarek impersonation), “Yeah, man I remember the last European tour we did …” And I’d go, “How long was your European tour?” And he’d go, “I don’t know. Six or seven shows?” Are you kidding me? That’s one of the things about the Doors. Nobody really realizes that they didn’t play that often. They actually went out on weekends. They’d jump on a plane, do a string of dates and come home. I think the most they went out for was a couple of weeks. Every show they’ve done has been documented and, not only has it been documented, but there’s been like a college thesis written about it.

Lollapalooza gets all the credit for merging youth culture and eclectic music, but your Gathering of the Tribes festival actually set the template

It’s kind of like you start a party and the next thing you know, you’re getting thrown out of your own party. Again, there’s a certain … hmmm, how can I say this diplomatically? If you behave, you’re allowed to play. If you don’t behave, you get blacklisted. You become the black sheep, the outsider. That’s one of the things about me as an individual … nobody’s got my number, nobody owns me. Once the business and the industry things started to kick in, I railed against that. I was, like, “I’m not going to do what you tell me to do.” And I wasn’t being reactionary, it was really about looking at something and saying, “I’m not a slave to this. This is my life, this is what I like, this is what I’ve chosen to do, I’m a creative person …” Once the door closes, then you’re out in the cold and you have to create your own situation.

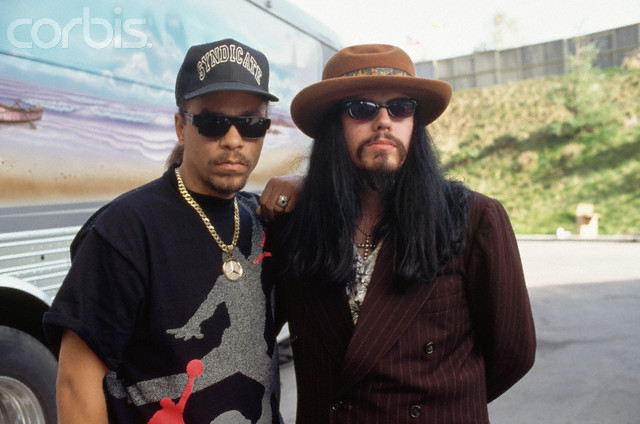

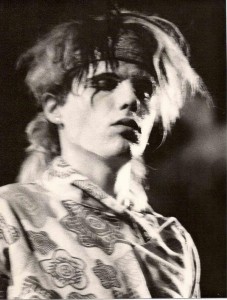

CHILLIN’: Ice-T and a villainous-looking Ian at the 1990 Gathering of the Tribes festival in San Francisco (photo by Neal Preston/CORBIS)

Gathering of the Tribes came out of a moment, of a feeling of altruistic intention. Tickets for Gathering of the Tribes were $10. It was put together by like-minded people. Bill Graham was the real catalyst. Once Bill Graham said he loved the idea and wanted to make it happen … We’re talking about Bill Graham! Everyone else can just go and fuck right off! His thing was, “MTV has created this situation where everybody is becoming so caught up in the narcissism of performance and commercialism…” I was looking at hip-hop culture, which I was a big fan of as well, and these guys weren’t getting a look. NWA wasn’t getting looked at. Public Enemy. They weren’t getting the kind of respect and airplay that they deserved in the late ’80s ‘cause it was still all Phil Collins, Bruce Springsteen and Sting. My idea was to get the rock camp to go over to the hip-hop community and say, “You know what? This is where we’re going. We want to showcase our generation.” And, of course, (I also wanted to include) all the post-modern bands. We approached everybody from Red Hot Chili Peppers to Stone Roses, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds … I had a list of maybe 200 artists. And the social and environmental groups came along as well, because the idea was to showcase our generation.

Public Enemy came on board and the Orange County Police Department basically said, “If they play, we’ll make it very difficult.” The community was terrified! You think back to the hip-hop shows of the late ’8os and people were terrified! NWA and Public Enemy were considered very dangerous bands that attracted a very dangerous audience. We ended up with Ice-T, Queen Latifah, Public Enemy … who didn’t actually get to perform, because of the pressure from the community. We had the Cramps, Soundgarden, Iggy Pop, Steve Jones, Mission UK, the Indigo Girls, Michelle Shocked. The amazing thing was that when we performed in San Francisco, Joan Baez came out and performed. She was astute enough to know that this is where the energy was and this is where we are moving forward. So, in many ways, it became an architectural cornerstone of where we find ourselves today.

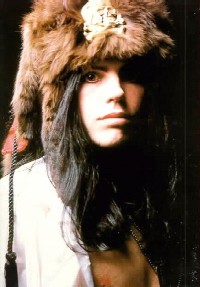

WARRIOR SOUL: Astbury’s Gathering of the Tribes music festival was inspired by a visit to a Sioux reservation while on tour with Metallica.

But you were there first

I was there first, because I was on tour with Metallica and we were in Pine Ridge, South Dakota and I ran into a Native American … an aboriginal American gentleman who invited me to his home to sit down and just hang out. I looked at the conditions he was living in and I looked at the life he was living in America in the late 20th Century. He was living impoverished. He didn’t have running water in his home. He had black mold in his house and it was affecting his children’s respiratory systems. He was studying in college to learn how to purify his tribe’s water supply. His goals and his aspirations and the integrity of this young man just destroyed me. He broke my heart. He didn’t even have a quarter to give to his daughter so she could buy an ice cream from the ice cream truck that came by. He had one can of Coca-Cola in the house and he split it with me. He invited me into his home, he broke bread with me. What he had, he shared with me. He didn’t know me from shit. He didn’t know I was a musician or anything. He was just interested in me because I was walking through Pine Ridge and he thought I was a native kid ‘cause I had long hair. I explained to him that I was just an English kid with long hair who was into Native American culture. He said, “Come back to my house and we’ll talk.” That night there was about 14 Lakota Sioux on our bus hanging out. I invited everybody. I went away (from that experience) and I thought I gotta do something. This is ripping me to pieces. That festival came out of those socio and economic, spiritual experiences.

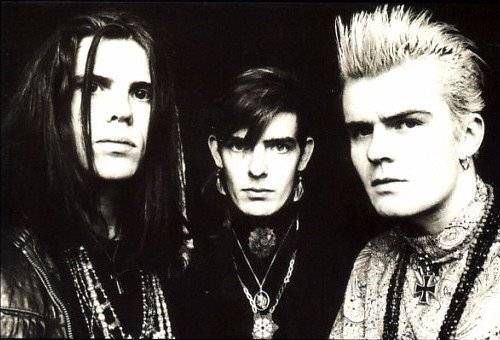

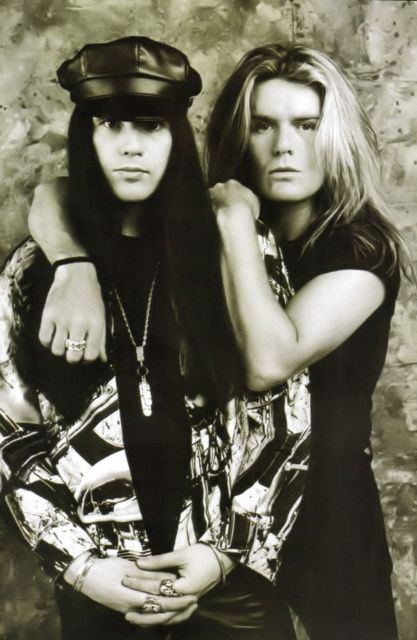

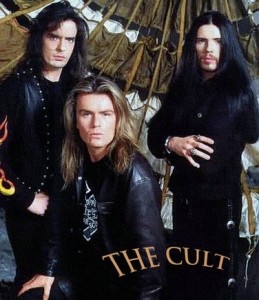

GENRE-BENDERS: In look, sound and vision, the Cult was one of the original alternative bands in more ways than one

But of course, we did our festival and it was observed by other Love Removal Machine aficionados who thought that it could be profitable so they said, “We’re going to go create one.” And, of course, it became a commercial event. Initially, I was very excited because I thought, “Wow, this is amazing, we’re going somewhere, we’re all moving, this is exciting.” Then three, four or five years later, it becomes very commercial and you look at it and go, “Wow, here comes the new boss, same as the old boss.”

The only reason Gathering of the Tribes didn’t continue is because Bill Graham died in a helicopter crash. We lost our main benefactor. Unfortunately. Sadly. He was a mentor to me. The Cult played the Filmore in 1985 when they reopened it. We played with the Morlocks. Bill Graham took me aside and goes, “Hey man, you remind me of Jimi and Janis.” He wanted me to take care of myself, because he could tell I was a hellion. I mean, none other than Bill Graham! Most kids today go, “Who’s Bill Graham?”

Without Bill Graham, we probably wouldn’t have the cultural diversity we have now. We wouldn’t have a Lady Gaga without Bill Graham. You know one thing I will say about her? She gets it. She understands the position she’s in as a performer, an entertainer. She’s an intelligent, brilliant, exciting, dynamic performer. She’s giving us the spectacle and she’s also giving us the music. She loves Queen, she loves Springsteen, she loves Elton John, etc. She loves Madonna. She talks about these things with passion and I really respect and admire her for that. In many ways, she’s radical. And I don’t mean radical in the sense that she wears exotic costumes. She’s radical in the sense that she’s pure of heart.

********************************************

To read my condensed March 2012 interview with Ian Astbury, go here. To read my 2001 interview with Cult guitarist Billy Duffy, go here. To hear bonus track, “Until the Light Takes Us,” from the upcoming new album, “Choice of Weapon,” click the video below

SXSW: The Cult plays three gigs during SXSW: March 16 at Waterloo Records (6 p.m./free to the public); March 16 at Klub Krucial (midnight/badges only); and March 17 at Auditorium Shores (8 p.m./free to the public).

Always liked this cat – he was esoteric and spiritual…looking forward to checking out his new sound…

Thanks for reading and posting Dan. Will be rocking with them on Saturday during SXSW.

Thanks for the excellent interview. I’d be interested in the full version if you can post it at some point.

Thanks for reading and posting, Batchainpuller (love the handle, Beefheart!). The full interview is up. Hope you enjoy

Epic Interview Dave! Thanks for your work. I am really missing out this year! Would love to read the parts sitting on the editing room floor someday. Will

Thanks, Will. Means a lot coming from a true Cult fan such as yourself

I’m a big fan of the Cult. Love the dynamic and caring conscience of Ian Astbury. I am thankful that Makoyepuk (Ian Astbury), Billy Duffy, Chris Wyse and John Temptesta are in the Cult. All things intersect for a reason. Loved the interview Metal Dave. Seriously did you tag him with Wolf Child or was it a mutual thing? I have always known him as Brother Wolf. Hmmm maybe its a bad on me. I don’t know him personally. LOL much love and peace

Chris, thanks for reading and posting. I’ve always thought of Ian as “Wolf Child,” because of his lyric in “Wildflower” and because it just seems fitting due to his penchant for all things “earthy” and wild.

Ian’s a great guy, interesting read, thanks!

Thanks for reading and posting, Kitty. I appreciate you taking the time

I loved how Ian described how the music is created. Beautiful interview Thank you both.

Thanks for reading and posting, Stacy. Appreciate it

Great interview, Dave! You asked the good questions and got the good answers.

Thnx, Kristin. Appreciate you reading and posting. Keep it up!

Hi Guys! It’s Dana Frank, the photographer that shot the Group shot of Matt Sorum, Axl, Ian & Izzy. Could someone please contact me? There are corrections that need to be made to your caption. Thanks! Dana

Hey Dana, thanks for reading and being in touch. How can we correct the photo caption?